Shared Memory

Contents

Shared Memory¶

The asynchronous scheduler accepts any concurrent.futures.Executor

instance. This includes instances of the ThreadPoolExecutor and

ProcessPoolExecutor defined in the Python standard library as well as any

other subclass from a 3rd party library. Dask also defines its own

SynchronousExecutor for that simply runs functions on the main thread

(useful for debugging).

Full dask get functions exist in each of dask.threaded.get,

dask.multiprocessing.get and dask.get respectively.

Policy¶

The asynchronous scheduler maintains indexed data structures that show which tasks depend on which data, what data is available, and what data is waiting on what tasks to complete before it can be released, and what tasks are currently running. It can update these in constant time relative to the number of total and available tasks. These indexed structures make the dask async scheduler scalable to very many tasks on a single machine.

To keep the memory footprint small, we choose to keep ready-to-run tasks in a last-in-first-out stack such that the most recently made available tasks get priority. This encourages the completion of chains of related tasks before new chains are started. This can also be queried in constant time.

Performance¶

tl;dr The threaded scheduler overhead behaves roughly as follows:

200us overhead per task

10us startup time (if you wish to make a new ThreadPoolExecutor each time)

Constant scaling with number of tasks

Linear scaling with number of dependencies per task

Schedulers introduce overhead. This overhead effectively limits the granularity of our parallelism. Below we measure overhead of the async scheduler with different apply functions (threaded, sync, multiprocessing), and under different kinds of load (embarrassingly parallel, dense communication).

The quickest/simplest test we can do it to use IPython’s timeit magic:

In [1]: import dask.array as da

In [2]: x = da.ones(1000, chunks=(2,)).sum()

In [3]: len(x.dask)

Out[3]: 1168

In [4]: %timeit x.compute()

98.4 ms +- 510 us per loop (mean +- std. dev. of 7 runs, 10 loops each)

So this takes ~90 microseconds per task. About 100ms of this is from overhead:

In [5]: x = da.ones(1000, chunks=(1000,)).sum()

In [6]: %timeit x.compute()

2.08 ms +- 11.1 us per loop (mean +- std. dev. of 7 runs, 100 loops each)

There is some overhead from spinning up a ThreadPoolExecutor each time. This may be mediated by using a global or contextual pool:

>>> from concurrent.futures import ThreadPoolExecutor

>>> pool = ThreadPoolExecutor()

>>> dask.config.set(pool=pool) # set global ThreadPoolExecutor

or

>>> with dask.config.set(pool=pool) # use ThreadPoolExecutor throughout with block

... ...

We now measure scaling the number of tasks and scaling the density of the graph:

Linear scaling with number of tasks¶

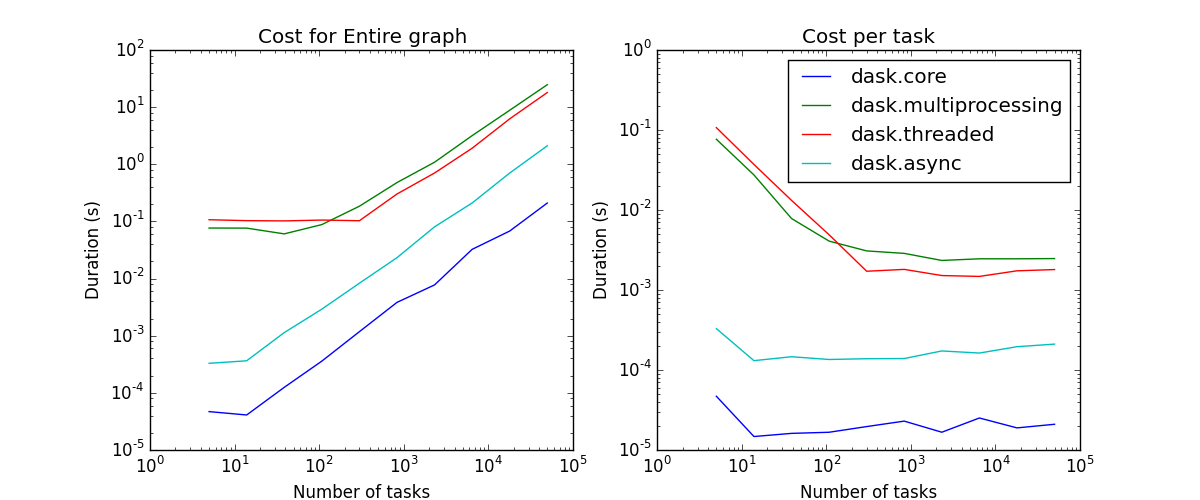

As we increase the number of tasks in a graph, we see that the scheduling overhead grows linearly. The asymptotic cost per task depends on the scheduler. The schedulers that depend on some sort of asynchronous pool have costs of a few milliseconds and the single threaded schedulers have costs of a few microseconds.

Scheduling overhead for the entire graph (left) vs. per task (right)¶

Linear scaling with number of edges¶

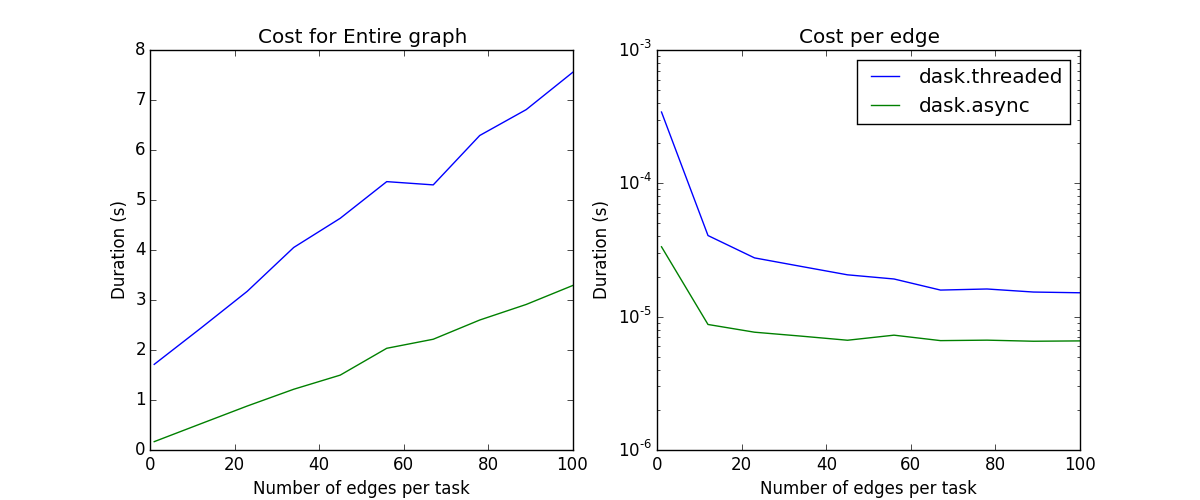

As we increase the number of edges per task, the scheduling overhead again increases linearly.

Note: Neither the naive core scheduler nor the multiprocessing scheduler are good at workflows with non-trivial cross-task communication; they have been removed from the plot.

Scheduling overhead of the entire graph (left) vs. per edge (right)¶

Known Limitations¶

The shared memory scheduler has some notable limitations:

It works on a single machine

The threaded scheduler is limited by the GIL on Python code, so if your operations are pure python functions, you should not expect a multi-core speedup

The multiprocessing scheduler must serialize functions between workers, which can fail

The multiprocessing scheduler must serialize data between workers and the central process, which can be expensive

The multiprocessing scheduler cannot transfer data directly between worker processes; all data routes through the main process.